Article by Camilla Baier

Lupine Travel continues its new Adventure Series: a collection of trips designed for curious, active travellers looking to go beyond the usual paths. Designed by Lupine’s Robert, each journey explores remote landscapes, challenging trails, and vibrant local culture. For this second exploratory trip, we travelled to Greenland, a land shaped by ice, silence, and endurance. From the colourful harbour of Nuuk to the vast fjords and frozen horizons of Ilulissat and Disko Island, this journey took us hiking at the edge of the Arctic world.

As we head north from Nuuk in a 32-passenger Air Greenland plane (compact, cosy, and full of anticipation) along the coast, the view below is mesmerising: fjords and archipelagos stretch out like a patchwork of icy blues. Definitely book a window seat, because not just the flight north but also the descent into Ilulissat Airport is jaw-dropping. The water below speckled with pristine, blinding-white ice floes and icebergs, each one so still it feels staged. The airport itself is also ridiculously charming, painted in pastel blue and pink like something out of a Wes Anderson film.

Ilulissat is not small by Greenlandic standards (about 4,500 people live here), but it feels wonderfully remote. A scatter of colourful wooden houses are perched against dramatic Arctic backdrops, painted bright red, yellow and green. In winter, under snow, this must look like Santaland. But even in summer, it feels impossibly removed, and you can’t help but feel a sense of excitement to have made it this far north.

Our first stop is the Icefjord Centre, an architectural marvel overlooking the Kangia Icefjord, already 250 km north of the Arctic Circle. The building blends seamlessly into the landscape, and inside, you learn how deep the story of ice really runs here, with an exhibition that weaves together the area’s geology, glaciology, and Inuit cultural history.

From there, we set out on a 3 km hike leading towards stunning fjord viewpoints. The glacier of Ilulissat Icefjord is known as the Sermeq Kujalleq Glacier. This is one of the world’s most active and productive glaciers, and it calves over 35 km3 of ice a year. During our hike along the coast of Ilulissat, we were able to walk on the land where the ancient Sermermiut Inuit settlement used to be. Now an expanse of bog adorned with a wooden walkway, this land is the perfect place to explore the millennary history of the Inuit while having the backdrop of the most impressive icebergs drifting along the icefjord.

The trail leads you past the Ilulissat dog station, where hundreds of sledge dogs doze in the sun, each tied to its wooden hut. Signs ask visitors not to pet or feed them – a rule that feels cruel at first, especially with the puppies tumbling over each other in play just out of reach. But these are working dogs, bred for endurance and discipline. And although sledging season now runs only from December to late April (shortened by climate change), this is their time to rest – and it’s important to respect the rules that protect both dogs and visitors. There are roughly 5,000 of them in Ilulissat, more dogs than people, and as we walk back, they start to howl in unison, a haunting, orchestral chorus that fills the air. At the Icefjord Centre, one of the narrators on the audioguide says, “The sound of dogs is the sound of Ilulissat,” and it’s true. But not only that, but it becomes the soundtrack of our Greenland journey, echoing from every valley we pass through in the next two weeks.

Our next leg takes us by ferry (a small 12-passenger boat) across Disko Bay. Skimming through a sea dotted with icebergs so luminous it hurt to look at them for long. The captain wove between floes with casual precision as we gawked, filming, photographing, trying and failing, to capture scale. The water’s colour actually defies description: crystalline blues and greens, otherworldly in their clarity. It feels like sailing through a Blue Planet sequence.

We’re lucky to have perfect weather as we approach the intriguingly named Disko Island; To locals, the island is Qeqertarsuaq; simply “Big Island.” Disko, however, seems to have originated from early explorers’ maps, perhaps inspired by its rounded shape or a mistranslation passed along by whalers. No one really knows for sure. Whatever the origin, it feels entirely fitting – after all, if any island deserves a name this cool, it’s this one. The main settlement, also called Qeqertarsuaq, greets us with its trademark colourful houses, perched along the coast against a backdrop of glittering icebergs.

That evening, we strolled to the black beach, which with its fine black sand, a remnant of the island’s volcanic origins, was still lit by the midnight sun. It never really gets dark here; time seems to stretch, and yet you’re never tired. Towering above the town of Qeqertarsuaq is Lyngmark Glacier, which we’d climb in the following days, weather permitting.

Alas, the next morning the weather turned; our luck had to run out sometime. Wrapped into every waterproof layer we had, we made our way towards the whalewatching shelter and hydrophone. Installed at Qaqqaliaq Lighthouse, the hydrophone captures the underwater soundscape in real time, streaming bowhead whale songs, calving icebergs, and other marine life via a 4G link for public access. Even though we neither saw nor heard whales that day, the climb itself was worth it: the scramble rewarded us with dramatic seascapes and the strange, quiet thrill of being at the edge of this rugged island.

Later that day (remember the sun never truly sets, so you start hikes at 7pm), we head in the opposite direction to the Kuannit cliffs. Just outside Qeqertarsuaq, we pass the small heliport and what must be the world’s most spectacularly located football pitch:

We cross a colourful bridge over Kuussuaq River, also known as Røde Elv (Red River), and are taken by how the water brings life to mosses, wildflowers, and the large and edible Angelica plant – kuannit in Greenlandic. Every summer, the locals harvest it to eat raw as a snack or use it in traditional Greenlandic cooking. As we continue along this lush stretch of volcanic coastline, we are soon surrounded by steep cliffs, cascading waterfalls, and towering basalt columns, their hexagonal shapes formed by lava flows that cooled rapidly below sea level. Interesting to note here is that geologically speaking, Disko Island is much younger and in that sense, very different from mainland Greenland, where the bedrock is billions of years old. The island was formed by volcanic activity “only” 50-60 million years ago. So, cinematically speaking, if the ferry crossing was Blue Planet, Kuannit feels straight out of Jurassic Park.

The next day brings our most challenging hike: the ascent to Disko Island’s iconic landmark Lyngmark Glacier (Lyngmarksfjeldet in Danish, Akuarut in Greenlandic), with its steep, layered rock slopes reaching nearly 1,000 metres. The path starts gently, winding through lower slopes marked by cobalt-blue cairns.

The climb gradually steepens, but frequent stops to admire the view make it manageable: Qeqertarsuaq shrinking below, Disko Bay stretching into the distance and icebergs dotting the horizon in every direction.

Fresh snow from the night before greets us at the summit, where we find Uunartuarsuup Sermia, one of Disko Island’s permanent glaciers. Nearby, the Disko Mountain Lodge perches at the glacier’s edge, offering panoramic views over surrounding mountains and valleys to the south and the entirety of Disko Bay to the north.

The descent is punctuated by another sledge dog symphony, their howls echoing across the valley. Back in town, we toast our glacier ascent with Qajaq local beer, resting our legs and soaking in our final view of Disko Bay before the ferry back to Ilulissat.

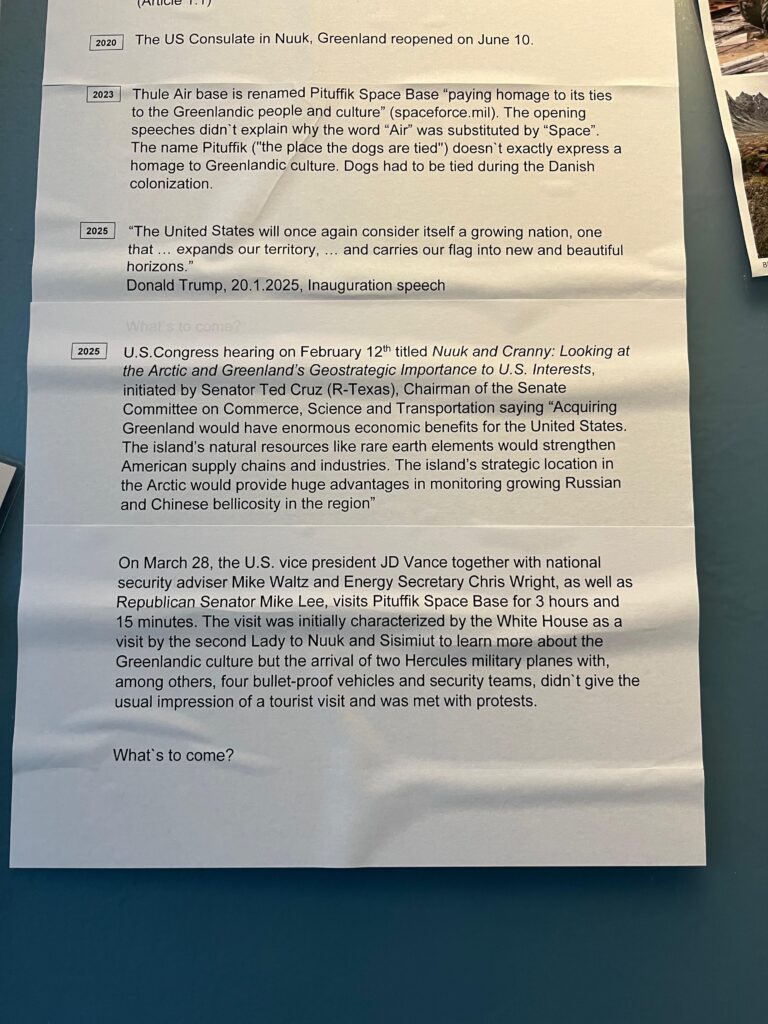

Back in Ilulissat, we explored the town’s quieter corners, including the Ilulissat Art Museum – one of only two art museums in Greenland. Visitors shuffle around in sealskin slippers to protect the floors of the 1923 building, a charming detail that sets the tone for the museum’s cosy, homey atmosphere. A personal highlight was discovering that the 1956 Greenlandic film Qivitoq was partially filmed here. We also visited the Knud Rasmussen Museum, dedicated to the famed Greenlandic-Danish polar explorer and anthropologist. Inside, the exhibitions trace his expeditions and contributions to “Eskymology,” but also the socio-economic and geopolitical history of Ilulissat, from halibut fishing to Greenland’s shifting ‘relationship’ with the U.S. (the latest entry in the “US and the U.S.” section dated March 2025).

That night, we boarded a small boat for our midnight cruise among the icebergs. Our local skipper navigates effortlessly through a maze of ice as we head south of Ilulissat, to the mouth of the Icefjord, while we roam the deck searching for the perfect view (spoiler: they all are!).

We’d brought our whisky flask from Scotland, and when we poured a dram, our guide smiled: “Do you want this on Arctic rocks?” He hauls a chunk of ice from the sea, chips it down, and serves us a drink straight from the fjord. The sound of ice cracking in the glass, with those insanely epic views, has spoiled any dram of whisky for the foreseeable future.

We spot a distant hunting boat and hear a few gunshots (we’re told it’s most likely sealing), then nothing but silence, sunlight, and drifting giants. We don’t see whales this time, but stepping off the boat past midnight, with the sun still illuminating the icebergs and refusing to fade, still makes this one of the highlights of the tour.

The next day, we enjoyed learning more about Ilulissat’s history on our city tour, but the real highlight (yes, yet another one) came later: the Greenlandic sled dog encounter.

After days of spotting chained dogs with “do not touch” signs, we finally got up close to a kennel of working Greenlandic sledge dogs. Dressed in overalls and wellies, we fed and cuddled them, learning about their training, how to handle them, and the strong bond between mushers and their dogs. We heard about their personalities, hierarchies, and the logic behind their chainings – necessary to prevent fights and maintain pack order. These were the same dogs we had seen tied up earlier, but here they revealed their soft, goofy, and affectionate sides.

The dog sledge is a deeply rooted symbol of Greenland, with a history stretching over 2,000 years. This means of transport has survived through millennia, retaining its basic principles dating back to the Viking Age. Despite their working status, the dogs are warm and playful once you enter their world, making goodbyes, especially to the puppies, was particularly hard.

We’d been told you can’t truly say you’ve travelled through Greenland without taking to the sea, so we boarded the overnight Arctic Umiaq coastal ferry back to Nuuk. This is the only coastal passenger ferry in Greenland, and something of an institution here.

Unlike Arctic cruises designed for tourists, Arctic Umiaq mostly carries locals. Although we spotted a few other tourists like ourselves, the majority of the passengers were families visiting relatives, workers heading to the next port, or students on their way home. The ferry makes a handful of brief stops at remote towns and settlements along the west coast. Most are so fleeting you can’t disembark, but from the deck you can watch small boats pull alongside; crates being unloaded, someone waving goodbye, or a new passenger stepping aboard. For many of these communities, the ferry is their only mode of transport, linking them to the rest of Greenland.

It’s also one of the most beautiful ways to travel. From the deck, we watched humpback whales breach in the distance and seabirds glide alongside, while panoramic windows around the ship offered endless views of shifting light and coastline. Below deck, the berths were surprisingly comfortable and private, and we slept soundly as the ship hummed its way south through the night.

Back in Nuuk, we visit the Greenland National Museum, nestled in a cluster of traditional Danish buildings in the old colonial harbour. The exhibits trace Greenland’s 4,500-year history – from the first Arctic Stone Age cultures and Norse settlements, to the arrival of the Thule culture, ancestors to today’s Inuit, and the gradual transition to modern Greenland.

One of the most remarkable exhibitions was the Qilakitsoq mummies: four women and two infants discovered near Uummannaq in northwest Greenland. Their traditional Inuit face tattoos are still faintly visible, a haunting connection between ancient and modern Greenlandic identity. Look for the nearby special display that explains how these tattoos are making a comeback, being reclaimed by younger generations of Inuit women.

We were also captivated by the Pearyland Umiaq, the world’s oldest nearly intact skin boat, whose well-preserved remains are estimated to date back to the 1470s – a tangible link to Greenland’s enduring maritime traditions.

We finished our trip at Kittat Ecomuseum, where a small group of women designers create and care for traditional Greenlandic costumes. They sew the intricate avittat skin embroideries, cleanse and prepare skins, design beadwork, repair old garments, string up skins for winter bleaching, and make other parts of the complex and beautiful traditional costume.When we visited, one designer was working on a thigh-high sealskin boot, exquisitely detailed and painstakingly stitched, and answering every question as she works, a final reminder of Greenland’s generosity, artistry and spirit.

—

Reflections

From the pastel airports to volcanic cliffs, sledge dog symphonies to midnight whisky on Arctic ice, Greenland defies every preconception. It’s both ancient and contemporary, quiet and full of sound, and impossibly vast.

Each place carries its own rhythm, and through it all, one thing remains constant: the feeling of being very, very small in the presence of something unimaginably big.

—

Check out the full itinerary and join Lupine in July 2026: Greenland – Hiking the Far North Tour

Camilla Baier is a German/Brazilian writer and researcher based in Edinburgh.

Follow Camilla on Instagram: @camilla_baier

Keep In touch

Make sure you never miss an adventure by signing up to our mailing list. Be the first to know about new tours and travel tips.